top of page

The history of francophone immigration in Canada

French-speaking colonists' immigration to the new continent significantly decreased after Acadia and New France were ceded to Great Britain. Less than a thousand people immigrated between 1760 and 1840. Nonetheless, these immigrants maintained close ties with French Canadians and Acadians. Due to the scarcity of educated individuals at the time, French-speaking educators, physicians, and attorneys were particularly welcomed. Some of these new subjects were from the French-speaking Anglo-Norman isles of Jersey and Guernsey, as well as Belgium and Switzerland. Among them were businesspeople and bankers who established and ran cod fisheries in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

After the rebellions of 1837-1838, the British Crown, under the new policy, replaced the Constitutional Act of 1791 with the Act of Union in 1840. This marked the establishment of the fourth constitution of Canada and united Upper Canada and Lower Canada into one province. The document advocated the adoption of Protestantism and English as the only official language to govern public affairs within the colony. This act stimulated the French Canadian Church to recruit members, by dozens of congregations and religious groups, based on their respective vocations, to establish a wide array of schools, hospitals, and orphanages covering French-Canadians from east to west. Various religious groups responded to the call. The Oblates opened missions to the Northwest, and the Jesuits, the Holy Cross Fathers, and the Eudists built classical colleges at Saint Boniface, Manitoba, Sudbury, Ontario, Memramcook, New Brunswick, and Pointe-de-l'Église, Nova Scotia. These members of the clergy led to a massive increase in the rate of French Canadian literacy. Literacy rose to 87 percent by 1910, up significantly from 26 percent in 1840.

The first immigration legislation, which occurred within the Canadian Confederation in 1869, encouraged the immigration of British colonizers, but not Catholics and Francophones. French-speaking Europeans could finally reach the goldfields of the Klondike, and professionals founded a number of Francophone communities, such as Victoria, on the west coast province of British Columbia. During the Mid-19th Century, the soil on the Canadian Prairies proved to be very rich. Canadian completion of the trans-Canada railway and Canadian government promotion of a farming "El Dorado" encouraged French priests to recruit French-speaking Europeans. French-speaking Europeans settled outside Quebec, most notably in the new towns of Grande-Clairière and Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes, Manitoba, and Ponteix and Saint-Brieux, Saskatchewan, to found churches, schools, and print French-language papers and various societies. In 1948, the Canadian government considered French-speaking Europeans to be as valuable to Canada as the British and Americans.

In 1967, Canada abandoned the use of place of origin as an immigration selection criterion, and sought instead to recruit professionals proficient in either English or French. This policy led to increased immigration to Canada, outside of Quebec, from the Caribbean, Arabic-speaking countries, and Francophone Africa. Simultaneously, the government endeavored to promote linguistic duality and multiculturalism as a means of reflecting the changing racial and ethnic makeup that informed its policies.

Contemporary Francophone immigration helps stimulate established institutions and create new ones. The Official Languages Act and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act set out the federal government’s commitment to fostering the health and development of minority language communities across Canada. These days, numerous settlement programs and community organizations support the welcoming efforts of Francophone communities outside Quebec and help promote the local and regional culture to attract many French-speaking newcomers and ensure their successful integration into our communities, our workplaces and our lives.

Old Mission House, built by French settlers in 1784

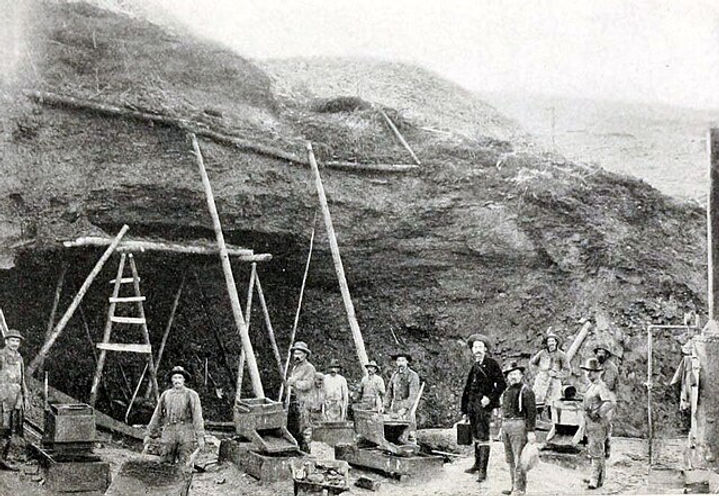

Klondike Gold Rush, 1899

bottom of page